Close-Out

Whether a program is large or small, is a component of an emergency response, or has been in place for an extended period, programs end or transition and must go through a close-out process. Planning for program close-out is as critical as designing its implementation, and you should devote equivalent effort early in the program development phase to plan for close-out. Preparation should include setting a specific end date and listing the activities that must be completed before that date.

These activities may include communicating about program close-out, obtaining final program data, finalizing processes for return of any supplies or equipment, and documenting lessons learned.

This Section addresses areas to consider when closing out a program, based on our experiences with the Zika Contraception Access Network (Z-CAN) program. Some domains are specific to a contraception program, and others may be adapted for any service delivery intervention or program. This Section includes guidance on closing out a program to increase access to contraception.

Effective communication is important. Communication efforts should be strategic throughout the program, but especially during a change or end of services. It is important to share with providers and staff what is happening, how it will affect them, what the next steps are, how to direct questions, and who will answer them (See Section 4).

Z-CAN Example: Communicating about Program Close-out

As Z-CAN program services ended, program leaders assessed communication needs of each stakeholder group and implemented the preferred mode of communication. The program leaders also strategically planned a timeline for notifying each stakeholder group to ensure they had an opportunity to hear updates when appropriate.

When you communicate early and honestly with partners about anticipated changes in a program’s services, partners feel included in decisions such as ending services, and they are able to assist with a smooth transition. Keeping partners informed also can start discussion among the program team about next steps such as planning for sustainability, dissemination of results, and other important tasks that will take place after services have ended.

Z-CAN Example: Communicating with Donors

When the final day of Z-CAN services was determined based on funding availability, the National Foundation for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Inc. (CDC Foundation) notified donors via e-mail of the end date. We communicated in these e-mails that although services were ending, the team was still hard at work transitioning the program to close-out. We shared brief dissemination plans, including the opportunity to collect lessons learned from local partners that would inform sustainability strategies. CDC Foundation also offered donors the opportunity to schedule update calls before submitting final reports.

Lessons Learned: Keeping Communication Channels Open

Effective stewardship builds trust among donors and other key stakeholders. Throughout the Z-CAN project period, the CDCFoundation and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) conducted joint conference calls to update donors and partners.

Furthermore, the CDC Foundation and CDC held regular conference calls, email interactions, and in-person meetings with local Puerto Rico partners. Maintaining regular communications with key stakeholders built trust among the team and stakeholders, which facilitated a smooth transition during program closure. Keeping the channels of communication open allowed key stakeholders to ask questions and stimulated dialogue around next steps, sustainability, and lessons learned.

As key stakeholders and a gateway to patients, providers can play a crucial role in sharing program updates. When providers and staff receive program updates, they can make necessary changes in their clinical practices and assist in notifying their patients. Clinic staff can post notifications in waiting rooms, patient rooms, and other common areas, and they can share updates verbally during registration or checkout. Before clinical practices can share program updates with patients, they must first have a mechanism to receive programmatic updates.

Z-CAN Example: Communicating with Providers

The Z-CAN program used a three-pronged approach—e-mail, telephone, and fax—to communicate the end of Z-CAN services to physicians. This ensured that physicians and clinic staff were aware of the critical program update. In addition to the three-pronged approach, we also posted the announcement in a callout box on the home page of the Z-CAN provider website with a link to frequently asked questions (FAQ). The FAQ documents served as a reference guide for physicians and clinic staff. Finally, Z-CAN physicians and staff were invited to a town hall meeting where they learned next steps to close out Z-CAN services at their clinics and had the opportunity to ask questions about the transition period.

Lessons Learned: Written Communications

Written communication such as an e-mail or letter can serve as a reference document for the audience (patients, providers, etc.). Letters or em-mails can provide contact information for questions and emphasize reminders about next steps. The letter sent to Z-CAN physicians reminded them about submitting forms, when to report an adverse event, bundled reimbursement for insertion and removal of a LARC, and other program information.

Lessons Learned: FAQ Documents

Two FAQ documents (one for physicians and one for patients) answered some of the most frequently asked questions about the ending of Z-CAN services. Once developed, the FAQs were posted on the appropriate websites. It was some of the common concerns. In addition, Z-CAN audiences could use these documents later as a reference guide.

RESOURCES AVAILABLE:

Deciding whether to retain a patient’s personal contact information may be a difficult decision. A program should never collect personal identifiable information (PII) without a plan for keeping the data confidential and private. If PII is collected, program staff must have clear guidelines for how data will be stored and used.

Communication with patients can be challenging, especially for contraceptive programs or interventions. In this context, your program may decide that program staff should not have access to patients’ contact information due to the sensitive nature of data collected. This decision limits communications modes that may be implemented. And yet, it is important to ensure that patients, the most affected group, receive critical programmatic updates, such as end of services, through at least one communication mode.

Z-CAN Example: Communicating with Patients

The program used two main channels to communicate with women about the last day of Z-CAN services: Ante La Duda, Pregunta (ALDP) website and the ALDP Facebook page. We posted and promoted a program announcement on the Facebook page to ensure as many visitors as possible could see this programmatic announcement. On the website, we posted a callout box with the announcement and an FAQ document to assist women with questions they had pertaining to the transition. Women also were able to contact the local Z-CAN Puerto Rico staff with other questions via the hotline or e-mail.

Lessons Learned: Close-out

Once the project's closure was announced, it was important to use diverse methods of communication with key stakeholders who were immediately affected by the closure. It also was crucial to use agreed-upon standard language in stakeholder interactions to ensure the same message was delivered, no matter who was giving it or receiving it.

RESOURCE AVAILABLE:

Ensuring your data are as complete and accurate as possible is critical to providing a clear picture of the impact of your program. Quality control and quality assurance efforts should be ongoing throughout your program (See Section 5), but final efforts at program close-out will still be needed. Build enough time into the total program timeline to allow for thorough, systematic review of the data and follow-up with providers to obtain missing data or clarifications for data already submitted after services have ended (See Section 2.6).

Z-CAN Example: Final Data Collection

Services ended on September 23, 2017, but work continued for the Z-CAN program staff. Z-CAN physicians still had to submit final forms, and the data were still undergoing quality control and quality assurance reviews for completeness and accuracy. Efforts to obtain missing data and clarifications intensified during this period as staff focus shifted away from processing incoming data. The Z-CAN team initially estimated that the final data set would be ready by December 31, 2017. During the final month of the Z-CAN program, however, Puerto Rico was affected by two devastating hurricanes, so the timeline for final data collection and cleaning was extended to the first week of March.

Lessons Learned: Ongoing Data Management

Having a well-developed system for processing and cleaning data throughout the length of the Z-CAN program was essential to managing the large number of records submitted by providers. The Z-CAN patient database contains over 40,000 records (Initial and Return Visits). While time was needed for final data collection and cleaning, the burden was much less than it would have been if data management efforts had not been ongoing (See Z-CAN Examples in Section 2.6 and Section 5).

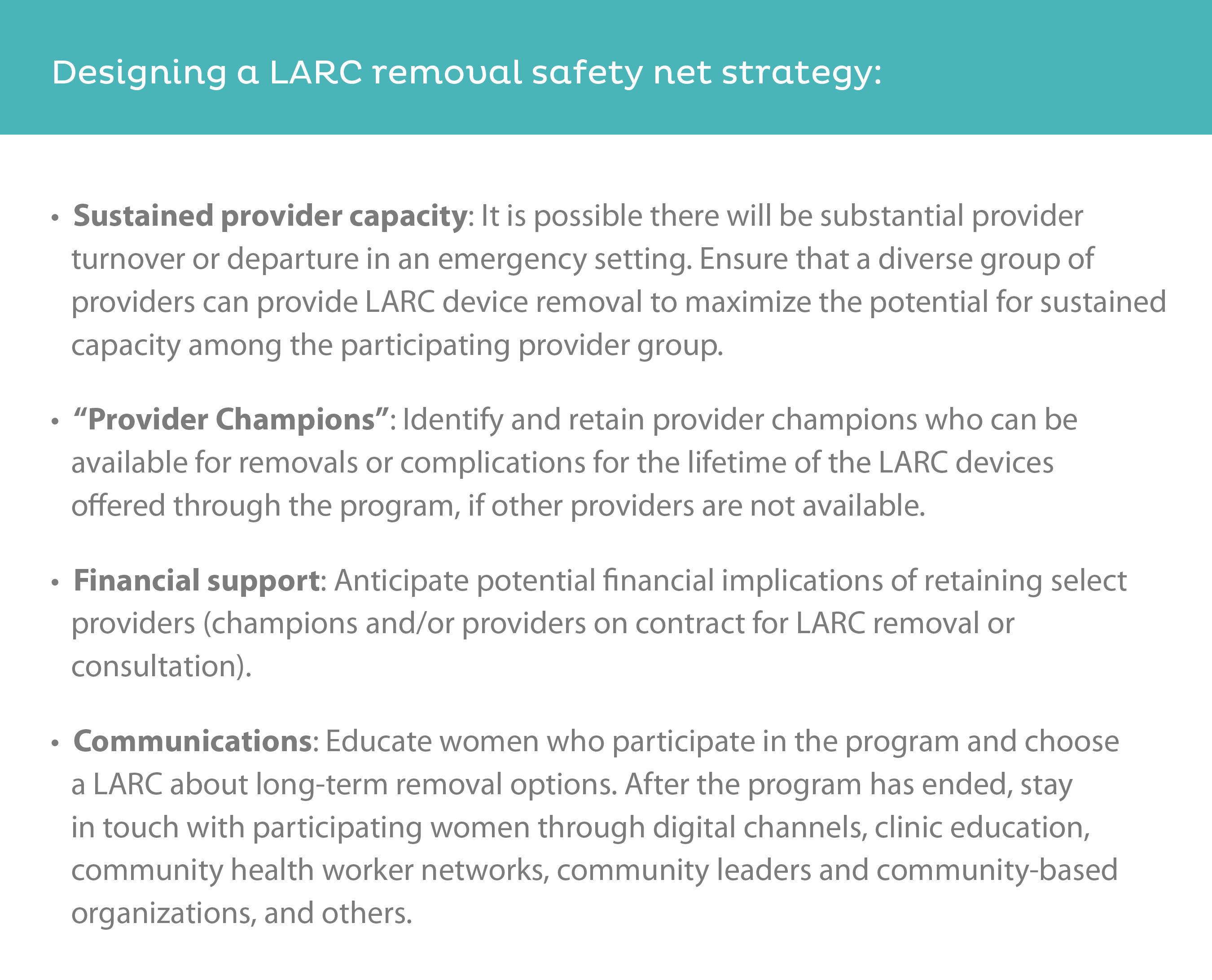

It may be possible to build sustainable services before the end of a short-term contraception program that is implemented and scaled in response to an emergency. But services may end before sustainable long-term services are in place. When this happens, the program must anticipate the need to remove LARC devices beyond the lifetime of the program. Use these tips to build a long-term removal plan into the program design.

Designing a LARC removal safety net strategy:

- Sustained provider capacity: It is possible there will be substantial provider turnover or departure in an emergency setting. Ensure that a diverse group of providers can provide LARC device removal to maximize the potential for sustained capacity among the participating provider group.

- "Provider Champions": Identify and retain prvider champoins who can be available for removals or complications for the lifetime of the LARC devices offered through the program, if other providers are not available.

- Financial support: Anticipate potential financial implications of retaining select providers (champions and/or providers on contract for LARC removal or consultation).

- Communications: Educate women who participate in the program and choose a LARC about long-term removal options. After the program has ended, stay in touch with participating women through digital channels, clinic education, community health worker networks, community leaders and community-based organizations, and others.