Monitoring & Quality Assurance

An essential part of any program or intervention is to collect and review programmatic information to ensure that all participants receive high-quality programs or services. This means developing and using a system to collect and monitor information that will help you identify indicators of successful implementation, alert you to challenges in program delivery, or identify the need for additional training. Setting up systems, procedures, and communication channels to capture programmatic information from patients and providers is all part of the process of monitoring and quality assurance.

This Section shares information and insights into critical aspects of monitoring and quality assurance for a program that increases access to contraception.

Data collected for your program can be used to monitor program activities (See Sections 2.6 and 3.2). The types of data collected, how often data are reviewed, how the data are presented, and the follow-up actions required will vary depending on the goals of your program. Ensuring the data being collected are as informative as possible requires ongoing quality control and quality assurance reviews. These reviews can be conducted in various ways and depend on how much data you have and the resources available for summarizing and analyzing the data.

RESOURCES AVAILABLE:

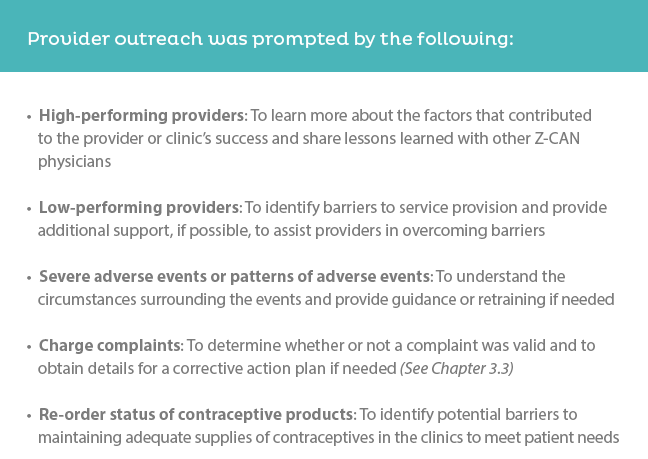

Z-CAN Example: Using Data to Identify When It Is Time for Provider Outreach

Z-CAN program data were used to provide guidance to program staff about Z-CAN physicians or clinics that should be scheduled for a provider outreach call or site visit.

Provider outreach was prompted by the following:

- High-performing providers: To learn more about the factors that contributed to the provider or clinic’s success and share lessons learned with other Z-CAN physicians

- Low-performing providers: To identify barriers to service provision and provide additional support, if possible, to assist providers in overcoming barriers

- Severe adverse events or patterns of adverse events: To understand the circumstances surrounding the events and provide guidance or retraining if needed

- Charge complaints: To determine whether or not a complaint was valid and to obtain details for a corrective action plan if needed (See Chapter 3.3)

- Re-order status of contraceptive products: To identify potential barriers to maintaining adequate supplies of contraceptives in the clinics to meet patient needs

RESOURCES AVAILABLE:

Lessons Learned: Provider Outreach and Quality Assurance

Establishing regular meetings with program staff to discuss provider outreach efforts will help to ensure that there is a plan in place for all required follow-up. These meetings also provide a forum for discussion to identify lessons learned that would be helpful to communicate to other providers and clinic staff participating in the program. A Z-CAN newsletter was distributed monthly to Z-CAN physicians and staff, with the content for the Z-CAN newsletter based on information obtained during provider outreach activities.

RESOURCE AVAILABLE:

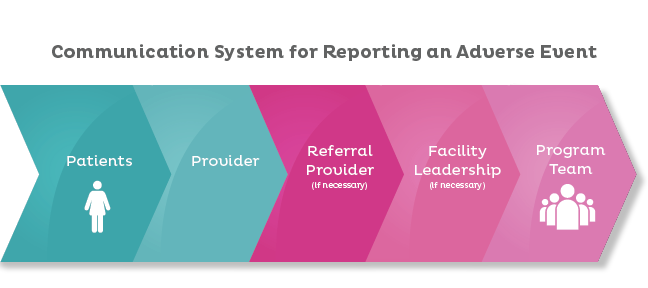

Any time a program involves provision of any clinical or other type of services, it is imperative to examine the potential for unanticipated side effects, unanticipated outcomes, and adverse events. In a contraceptive program, the team members should have sufficient subject matter expertise to understand what side effects, anticipated or unanticipated, or adverse events and severe adverse events could happen. This will aid in the design of counseling scripts or other materials and will assist the program in designing a mechanism for tracking, reporting, and managing adverse events. The primary focus of an adverse events tracking system is to help patients receive the care they need in a timely fashion and to make sure there is appropriate, high-quality follow-up until the event is resolved.

Adverse event tracking also is important for the purposes of program surveillance, reporting, and quality improvement of the program. Each program will need to develop a tracking database as well as a standard operating procedure (SOP) for management and follow-up of adverse events.

Z-CAN Example: Using Adverse Event Reporting for Quality Assurance

For the Z-CAN program, we designed a specific form for physicians to submit if they were notified of or identified an adverse event in one of their patients. The form included, for example, events that were not severe and events that served to track devices that were not usable due to failed insertions. Physicians were counseled at the time of their Z-CAN training on the management of select severe adverse events and the process for reporting adverse events and severe adverse events, and received an adverse event reporting algorithm as part of their procedure manual. Internally the program developed an SOP that helped guide the program team through programmatic management of the adverse events. The SOP enabled program staff to recognize adverse events trends among specific physicians and mapped out criteria for phone call follow-up, in-person follow-up, probation, and expulsion from the program, if needed.

RESOURCES AVAILABLE:

When starting a new intervention, program, or service that includes building or strengthening a network of providers—nurses, physicians, certified midwives, traditional midwives or others—it will be important to design a mechanism for communication with the network of providers. Communications may include notification of meetings, changes in standards of care, new scientific evidence that may support care provision, new or updated programmatic or procedural information, or other communications that support providers to continue delivering high-quality care. How the program communicates with the network of providers will depend on the setting and what modes of communication are available, reliable, and preferred. This may include an e-mail listserv, setting up a provider-only website where information can be posted, a text-based listserv, a phone-chain system, in-person visits, or a mix of these channels. Providers also will need a secure and reliable way to contact the program if they have questions, concerns, or a need to report something immediately.

Z-CAN Example: Communicating for Quality Assurance

The Z-CAN physician and staff network included over 400 people. This made it impossible to communicate information applicable to the entire network through one-on-one phone calls. To communicate efficiently with the network, we used primarily a combination of website-based notifications, an e-mail listserv, and monthly newsletter. We also held regular webinars at the outset of the program to address significant changes or new evidence that would be important for physicians to incorporate into their practices and followed up with an e-mail and mail to ensure receipt of important and relevant information. Physicians could communicate with the program through office lines, program officers’ cellphones, or the Z-CAN e-mail box that was managed daily by program staff.

To serve patients well and address any programmatic concerns or complaints, there must be a reliable way for patients to communicate with providers and the program and to receive a prompt response. How patients communicate with a program will depend on the setting. Patients may be able to e-mail, call, or text, but they may have to make inquiries in person.

Through the data-tracking system, programs will receive patient data and reports of services provided from the provider network, but to understand fully how a program is carried out, the program staff should have a way to hear directly from and document any concerns or complaints from the patient.

Establishing a secure mechanism patients can use to report concerns or complaints to the program is highly important for quality of care. Patients should learn during their initial visit to the program how they can make an inquiry or a report in the most efficient way.

This may be communicated verbally or through patient-friendly materials that are written in languages and literacy levels patients can understand and placed in network waiting rooms, clinics, and offices where patients can readily see them. Patients also should understand that inquiries and reports to the program will be confidential unless they prefer otherwise.

Z-CAN Example: Mechanisms for Patient Inquiries

The Z-CAN program used the following channels to enhance patient communication and to provide a secure mechanism for patient inquiries: hotline, website, e-mail, posters, palm cards, after-visit materials (See Section 4.4).

If a program or intervention includes financing providers, clinics, administrators, or other infrastructure, or includes agreements about service charges, the program should have a mechanism for reporting unauthorized charges or charges to patients that violate program agreements. Any payments, expectations regarding charges or payments, and formal agreements should be part of the initial program training, and a systematic process to track and report unauthorized charges should be established.

Z-CAN Example: Unauthorized Charges

One of the identified barriers for women in Puerto Rico to access contraception prior to Z-CAN was the lack of appropriate financial support or reimbursement for physicians. To remove this barrier, the Z-CAN program provided modest reimbursement for physicians for contraception counseling and provision of methods, including insertion and removal of long-acting reversible contraception (LARC) methods. Physicians who inserted LARC methods were reimbursed for the cost of insertion and removal in a single bundled (combined) payment at the time of the insertion to ensure that women did not have to pay for services during or after the program. Now that the program has ended, when women return for a removal, they will not have to pay for that removal. Z-CAN physicians were aware of the Z-CAN payment strategy and formally agreed by signing a Memorandum of Understanding with the National Foundation for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Inc., stating understanding and agreement with the payment strategy prior to initiating any Z-CAN services. The program developed a reimbursement algorithm and an SOP to investigate claims of unauthorized charges to patients. Z-CAN physicians also signed an agreement with the program.

One aspect of quality improvement for any new initiative is receiving feedback from those who carry out the initiative. Developing a way to hear from providers about their experiences with the initiative—what is working, what is not, what could be improved, and what suggestions they may have—will serve only to help the program. Conducting exit interviews with providers who leave the program for any reason is one way to explore these issues.

Z-CAN Example: The Exit Interview

A small number of physicians left the Z-CAN program before it officially ended, and it was important to learn from them what informed their decisions to leave and how we could improve the program. We designed an exit interview to explore these issues.