Sustainability & Replication

It is important to begin any program or intervention with the end in mind. Sustainability—the ability to maintain at a certain rate or level—is a long-term goal for many health initiatives.

Yet programs at all levels and settings often struggle to maintain programming and its benefits over time. And without the ability to sustain a program or intervention, critical improvements in public health and clinical care outcomes can dissolve.

To maintain a program or intervention benefits long-term, program staff, in partnership with key stakeholders, must start by identifying the key program components to sustain. Program administrators also must assess the organizational and contextual factors in their setting that could affect program or intervention sustainability. Factors to consider for program sustainability include the political environment that supports, or opposes, your program; a consistent financial base for your program; a continued commitment from your stakeholders; the internal support and resources needed to effectively manage your program and its activities; and the use of data to inform planning and document results, including successes and lessons learned.

With knowledge of these critical factors, capacity for sustainability can be built into the planning and development phase to position the program or intervention for long-term success. This Section introduces strategies for building program capacity for an effective, sustainable intervention and shares how to apply Zika Contraception Access Network (Z-CAN) lessons learned to other settings.

It is critical to engage and maintain partnerships with key stakeholders in each program phase (planning, implementation, evaluation, sustainability). Stakeholders are individuals and organizations that have an interest in or are affected by your program or intervention. Stakeholders often increase credibility of program and sustainability efforts; help facilitate program activities or troubleshoot challenges in the implementation; and may advocate, fund, or authorize continuation or expansion of the program.

To increase long-term sustainability, the program can work closely with key stakeholders to develop a sustainability plan that includes defining:

- What program strategies and activities to sustain over time?

- Who will be responsible for implementing the activities?

- Who are the partners involved?

- What are the strengths and challenges for each strategy?

- What are the beginning and end dates and status of activities?

Z-CAN Example: The Role of Partnerships to Sustain Efforts to Provide Access to Contraceptive Methods after Z-CAN

Strong partnership development was critical in the design, implementation, and sustainability planning of the Z-CAN program. The program was built with a network of partners that included federal agencies, territorial health agencies, private corporations, and domestic philanthropic and nonprofit organizations in the continental United States and Puerto Rico. Based on the needs assessment (See Section 1.1) conducted in the program planning phase and input from key stakeholders, Z-CAN identified contraception access barriers and challenges and developed key strategies to build capacity and sustainability. Stakeholders determined that successful sustainability would be achieved by maintaining the elimination of the most pressing barriers addressed by Z-CAN, including strategies to continue to provide women in Puerto Rico with the full range of contraceptive methods at low or no cost, and with same-day access after the Z-CAN program ended.

Strategies to sustain high-quality contraceptive services in Puerto Rico after the Z-CAN ended included:

- Building capacity of a broad network of physicians to provide access to contraception

- Raising awareness among women of reproductive age in Puerto Rico about the availability of contraceptive methods

- Expanding the number of contraceptive service access sites

- Working with health plans in Puerto Rico (public and private) to eliminate prior authorization requirements and cost sharing

- Discussing development of a sustainable contraception method supply chain with manufacturers

- Negotiating pricing to improve contraception access, including long-acting reversible contraception (LARC) methods

Health systems are commonly defined as all public, private, and voluntary entities that contribute to the delivery of essential health services within a jurisdiction to meet the needs of target populations. Health systems include public health, providers of health care (hospitals, physicians), payors (public and private insurance), community-based clinics or programs, and patients. The barriers for contraception access across health systems, in general, often include:

- Provider – Shortage of physicians trained in insertion, removal, and management of LARC; inadequate reimbursement; high acquisition and stocking costs for LARC methods

- Financial – Inadequate physician reimbursement for actual cost of providing contraceptive services (screening for pregnancy intention, contraception counseling, insertion/removal of LARC, follow-up); high out-of-pocket costs for patients

- Logistical – Limited availability of the full range of contraceptive methods; limited availability of same-day access; high acquisition and stocking costs for LARC methods for physicians, hospitals, and clinics

- Administrative – Prior authorization, step therapy (requirements that a woman first try and fail on another contraceptive method before being given a costlier method [LARC])

- Patient – Lack of patient contraception education, lack of awareness about where to access contraceptive services, high out-of-pocket costs

Z-CAN Example: Addressing Health Systems Barriers

To address health systems barriers to contraception access in Puerto Rico, Z-CAN developed strategies to increase capacity and build long-term sustainability (See Section 2.5).

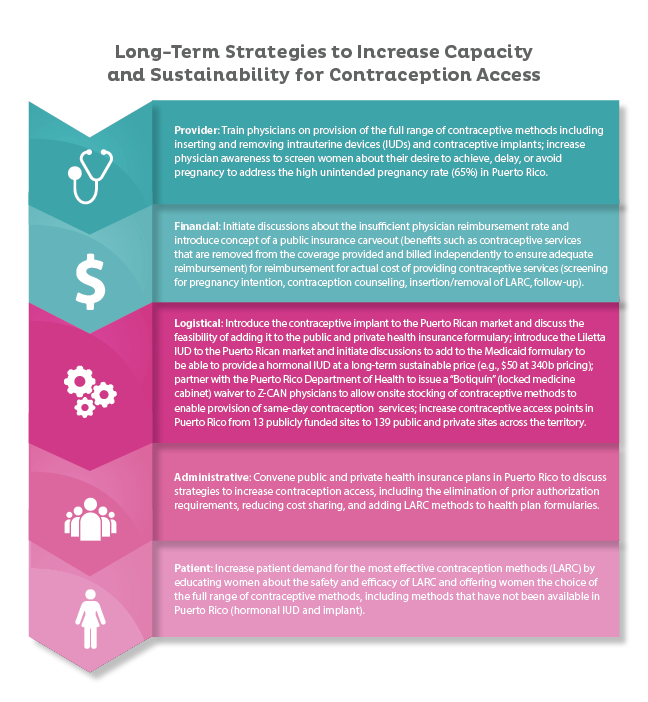

Long Term Strategies to Increase Capacity and Sustainability for Contraception Access

Provider: Train physicians on provision of the full range of contraceptive methods including inserting and removing intrauterine devices (IUDs) and contraceptive implants; increase physician awareness to screen women about their desire to achieve, delay, or avoid pregnancy to address the high unintended pregnancy rate (65%) in Puerto Rico.

Financial: Initiate discussions about the insufficient physician reimbursement rate and introduce concept of a public instance carveout (benefits such as contraceptive shrives that are removed from the coverage provided and billed independently to ensure adequate reimbursement) for reimbursement for actual cost of providing contraceptive services (screening for pregnancy intention, contraception counseling, insertion/removal of LARC, follow-up).

Logistical: Introduce the contraceptive implant to the Puerto Rican market and discuss the feasibility of adding it to the public and private health insurance formulary; introduce the Liletta IUD to the Puerto Rican market and initiate discussions to add to the Medicaid formulary to be able to provide a hormonal IUD at a long-term sustainable price (e.g., $50 at 340b pricing); partner with the Puerto Rico Department of Health to issue a “Botiquin” (locked medicine cabinet) waiver to Z-CAN physicians to allow onsite stocking of contraceptive methods to enable provision of same-day contraception services; increase contraceptive access points in Puerto Rico from 13 publicly funded sites to 139 public and private sites across the territory.

Administrative: Convene public and private health insurance plans in Puerto Rico to discuss strategies to increase contraception access, including the elimination of prior authorization requirements, reducing cost sharing, and adding LARC methods to health plan formularies.

Patient: Increase patient demand fro the most-effective contraception methods (LARC) by educating women about the safety and efficacy of LARC and offering women the choice of the full range of contraceptive methods, including methods that have not been available in Puerto Rico (hormonal IUD and implant).

Sharing program results with stakeholders, including key strategies, data, success and challenges, and lessons learned, is a critical piece to sustainability. Whether key stakeholders are interested in continuing the full program or intervention, or only key components, sharing all relevant information will make for a smooth transition. It also eliminates the need to re-invent strategies, materials, tools, and resources that already exist. Programs should consider regularly sharing data, success and challenges, and lessons learned with key stakeholders. In emergency response situations, stakeholders who are aware the program will be short-term may be motivated to continue the high-quality contraceptive services provided and plan sustainability efforts within the long-term.

Z-CAN Example: Sharing Lessons Learned

CDC and the CDC Foundation shared data, success and challenges, and lessons learned to help transition the Z-CAN program to a sustainable contraception access program led within the territory. CDC continues to be available for technical assistance as needed and requested by the Puerto Rico Department of Health and continues to provide technical assistance to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services- and Health Resource and Services Administration-funded grantees for their respective Zika Health Services grants. These grants have four components; one critical component is to increase access to contraceptive services for women and men. Additionally, CDC continues to provide technical assistance to the Puerto Rico Primary Care Association to support sustainable family planning services among the Health Resource and Services Administration-funded community health centers.

RESOURCE AVAILABLE:

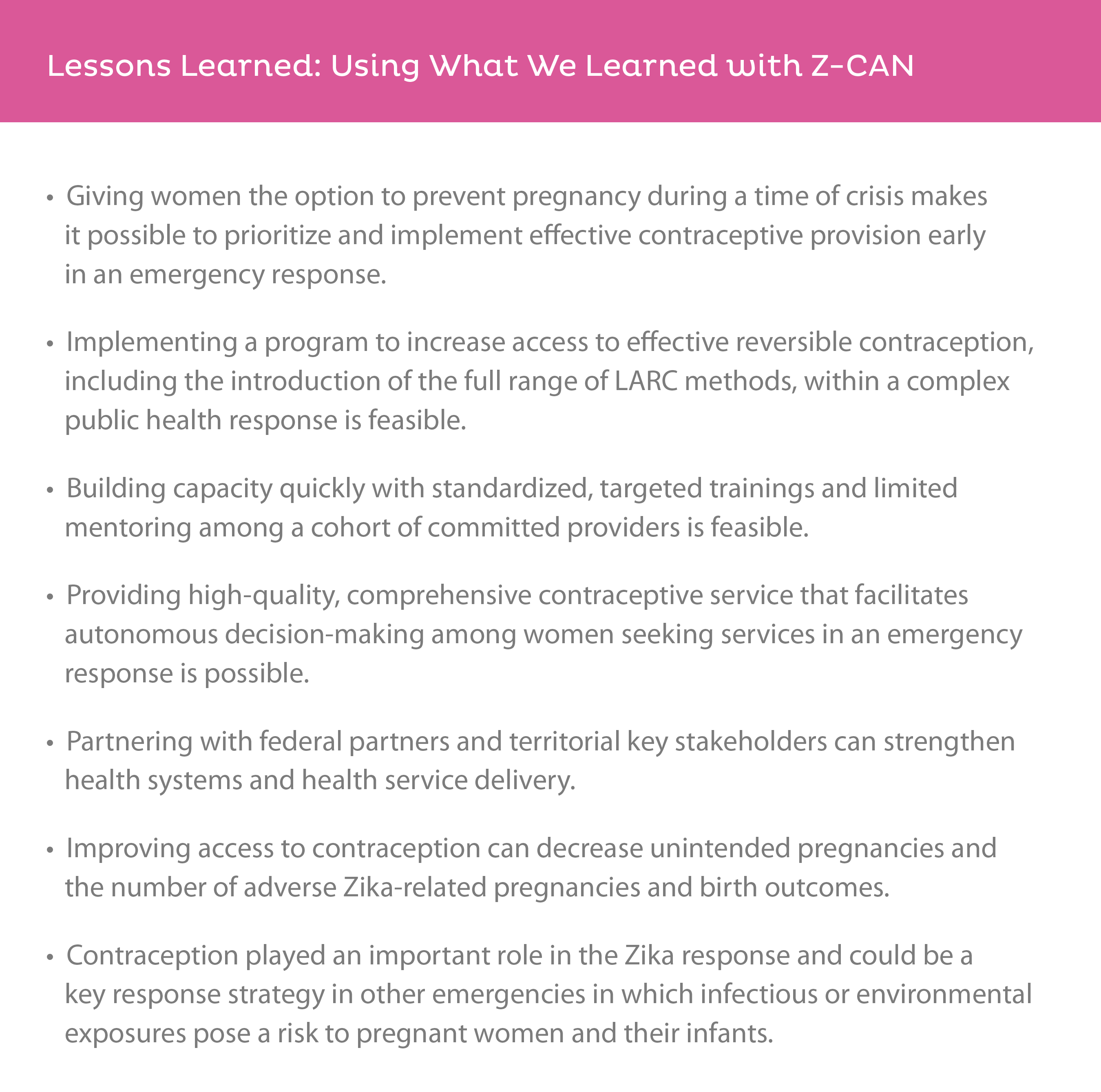

Lessons Learned: Using What We Learned with Z-CAN

- Giving women the option to prevent pregnancy during a time of crisis makes it possible to prioritize and implement effective contraceptive provision early in an emergency response.

- Implementing a program to increase access to effective reversible contraception, including the introduction of the full range of LARC methods, within a complex public health response is feasible.

- Building capacity quickly with standardized, target trainings and limited mentoring among a cohort of committed providers is feasible.

- Providing high-quality, comprehensive contraceptive service that facilitates autonomous decision-making among women seeking services in an emergency response is possible.

- Partnering with federal partners and territorial key stakeholders can strengthen health systems and health service delivery.

- Improving access to contraception can decrease unintended pregnancies and the number of adverse Zika-related pregnancies and birth outcomes.

- Contraception played an important role in the Zika response and could be a key response strategy in other emergencies in which infectious or environmental exposures pose a risk to pregnant women and their infants.

It is also important to share your program experiences and lessons learned with other key stakeholders and in other settings that may be interested in replicating the full or specific key strategies of the program or intervention. Documenting program design and implementation, communications with stakeholders during and after the program, and measurement and evaluation strategies is essential to sharing your experience and expertise with new settings. CDC has provided technical assistance on the key components of the Z-CAN program (See Section 1) to other U.S. territories and within the continental United States among settings with high risk for Zika transmission, including the U.S. Virgin Islands, U.S. Affiliated Pacific Islands, and state and local health jurisdictions, to increase access to contraception in the context of the Zika virus.

Z-CAN Example: Adapting Z-CAN Lessons Learned in Other Settings

CDC has applied lessons learned from Z-CAN to other settings with local and/or high risk for Zika transmission, including the U.S. Virgin Islands, U.S. Affiliated Pacific Islands, and Texas. This technical assistance has included:

- Needs Assessment on contraception access and provision (See Section 1.2)

- Formative research among women and men of reproductive age to assess knowledge, attitudes and beliefs regarding contraception use to determine optimal messaging related to knowledge of contraceptive options; contraception usage beliefs; barriers to accessing contraception; trusted sources of information; influencers; and preferred content, tone, messages, colors, and images in communication concepts (See Section 4.1)

- Development of a health communications toolkit, including health communication messaging (See Section 4)

- Training for providers on LARC insertion and removal using hands-on simulation, and complex cases (See Section 2.3)

- Training for providers and clinic staff on client-centered contraceptive counseling (See Section 2.3)

- Developing an action plan and monthly follow-up calls to track progress (See Section 5.1)

- Building capacity among territories, states, providers, and local community base